This year marks the 50th anniversary of the annual LGBTQ Pride Marchs, which were first held in June 1970 in numerous cities across the country. While most years, Pride has meant celebration, parade floats, and rainbow flags galore, it is as important today as ever to remember that the movement originally began not as a party, but as a fight. And at the forefront of this fight were numerous Black LGBTQ heroes whose stories have all too often been left out of the cannon of American Queer history.

One such hero was Marsha P. Johnson, a Black trans woman who was a leader in New York City’s gay rights movement. Today, Johnson is probably best known for her participation in the Stonewall Riots, a series of protests that began on June 28, 1969, when police raided a New York City gay bar called the Stonewall Inn. Though such raids on gay establishments were common throughout the 1960s, the Stonewall incident was unique because the club’s patrons resisted arrest and actually fought back against the police. The events of that night prompted several days of protests for LGBTQ equality. The next year, the first Pride Marchs were held to commemorate the Stonewall Riots.

In the 1960s, most gay bars in NYC were controlled by the Mafia, as the State Liquor Authority refused to issue liquor licenses to bars serving LGBTQ patrons. For the most part, the Mafia paid off the police so that establishments such as the Stonewall Inn could remain in business, though raids such as the one that occurred on July 28, 1969 still occurred from time to time. To learn more about the history of Mafia-led LGBTQ establishments, check out this article. Image found here.

The jury is still out on Johnson’s exact role during the night of the Stonewall raid. Some claim that Johnson “threw the first brick” at Stonewall—that is, that she was the first patron to fight back against the police. Other accounts—including one given by Johnson herself in an interview—argue that she didn’t actually arrive at the Stonewall Inn until after the fight had already begun; she came to the defense of her community, but didn’t start the riot herself. Still, a third set of sources claims that she wasn’t around at all that night.

Regardless of her attendance during the first night of the Stonewall Riots, Johnson definitely showed up for the rest of the movement, playing an active role in the demonstrations that followed. This is not surprising, as advocacy work was central to her life. Both before and after Stonewall, she regularly campaigned for the rights of gay, trans, HIV-positive, and homeless people. Together with Sylvia Rivera, another trans woman of color, she founded the organization Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries (STAR), which provided housing to homeless LGBTQ youth.1 Johnson managed to do all of this in the face of incredible adversity: not only did she experience racism and transphobia, but she was also homeless at times and relied on survival sex work to earn a living.

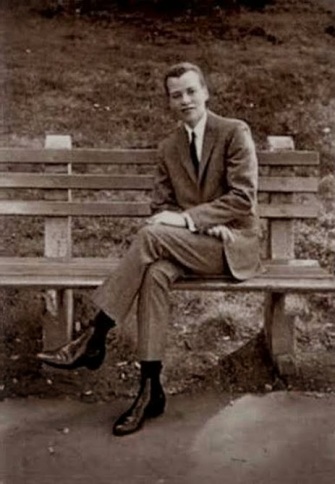

If Johnson wasn’t the one who instigated the Stonewall Riots, it very well could have been another Black LGBTQ individual, Stormé DeLaverie. Indeed, in 2008, DeLaverie—a biracial lesbian woman—admitted to having thrown the first punch at a police officer the night of the Stonewall raid. But DeLaverie’s legacy, like Johnson’s, also extends beyond her participation in the Stonewall Riots. Long before the Pride movement began, she was a member of the Jewel Box Revue, one of the first racially-integrated drag troupes in the United States, and performed as the group’s only drag king.2 Later in life, she worked as a security guard in New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood, which was home to many LGBTQ spaces, including the Stonewall Inn. DeLaverie was a fierce advocate for the gay community and for survivors of domestic abuse. Today, stunning photographs of her in men’s suits, taken by American photographer Diane Arbus, serve as a reminder of the role she played in changing societal perceptions around gender expression.

This photograph of Stormé DeLaverie, titled “Miss Stormé de Laverie, The Lady Who Appears To Be a Gentleman, NYC” was taken in 1961 by Diane Arbus, an American photographer who was known for capturing images of marginalized communities and individuals in New York City. Image found here.

While the Stonewall Riots were a pivotal moment in Queer history, the work of Black LGBTQ heroes was not confined to just New York City. In 1971, Donna Burkett and Maniona Evans—a Black lesbian couple living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin—received national media attention when they applied for a marriage license, despite the fact that same-sex marriage was illegal in all 50 states at the time.3 As expected, the couple was denied the right to be legally married, but they did get wed on Christmas Day of that year in a ceremony officiated by a local gay priest. Though their relationship ultimately didn’t last very long, their case nevertheless paved the way for important conversations about marriage equality.

A key theme that emerges in each of these stories is the role of intersectionality. Johnson, DeLaverie, Burkett, and Evans had to overcome barriers put in their way because of their racial, gender, and sexual identities. Each of these identities added another layer of hardship, and often, the overlap of these identities would create unique challenges. For example, growing up in New Orleans, Louisiana, DeLaverie was physically beaten by her classmates at school on several occasions for being biracial; it got so bad that her father had to send her to private school to protect her.4 When she realized she was gay around the age of 18, she moved to Chicago, knowing that her identity as a lesbian would not be tolerated in the South, either.

For some Black LGBTQ individuals, living at the intersection of these identities has moreover meant that their stories have been erased from history over time. How many of us today have heard of civil rights leader Bayard Rustin? As an advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., Rustin helped organize the 1963 March on Washington. In fact, he played a critical role in designing much of King’s platform of nonviolent protest by teaching King about Gandhi’s work in India. Yet, Rustin’s identity as an openly gay man—and particularly his 1953 arrest for “sex perversion,” a crime for which he was charged after he was caught having sex with another man—led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to downplay his contributions to the civil rights movement. At the time, the organization feared that his identity might impede their progress toward racial justice. (An important clarification: While this anecdote illustrates well the ways in which Black LGBTQ individuals can struggle to feel accepted in settings that are predominantly either Black or LGBTQ, it should not be interpreted as a rebuke on the Black community. After all, the reason the NAACP needed to worry so much about its image was because of racial discrimination propagated by white Americans. It’s worth noting, too, that one of Rustin’s most vocal critics was a white senator from South Carolina named Storm Thurmond).

These issues of intersectionality and the silencing of minority voices are not purely historical phenomena. Today, the Black LGBTQ community continues to face myriad challenges, some that are unfortunately all too reminiscent of the same ones that Rustin, DeLevarie, and their peers experienced over 50 years ago. These challenges include high rates of racially- and anti-LGBTQ-motivated violence, police brutality, homelessness, workplace discrimination, and disparities in access to healthcare.5 The latter issue has only been further exacerbated by the current coronavirus pandemic, as well as the recent decision made by the Trump administration to reverse existing healthcare protections for transgender Americans.

Still, there are many contemporary Black LGBTQ heroes who continue to pave the way for acceptance and equality, despite the persistence of these challenges. These heroes are people like Denise Simmons, former mayor of Cambridge, MA and the first Black, openly lesbian mayor in the United States. Or Ryan Russell, a former NFL player who recently came out as bisexual and now uses his platform to highlight issues such as homophobia in American professional sports. They are also people like country rapper Lil Nas X, who in 2019 broke the record for the longest-running number one single on the Billboard Hot 100 music charts, just a few weeks after coming out as gay. They’re heroes like Isis King, a Black transgender model and actress who is known for being the first-ever transgender contestant on the reality TV competition America’s Next Top Model.

As non-Black and/or non-LGBTQ allies, we need to do our part to support these heroes—and countless others whose platforms aren’t quite as large—in the fight against racism, homophobia, and transphobia. This starts by educating ourselves on Black LGBTQ history and contemporary issues. But it also means donating to and supporting organizations that are committed to issues at the intersection of race and sexual orientation; voting for politicians and local leaders who promote minority rights; and deeply interrogating the ways in which the organizations and systems we ourselves are a part of may exclude LGBTQ people of color.

This Pride more than ever, it’s important we reaffirm that #BlackLivesMatter and #TransLivesMatter. It’s important that we finally start showing it.

A new version of the LGBTQ pride flag is being flown at Pride Month festivities this year. This new flag emphasizes solidarity with communities of color, as symbolized by the black and brown stripes. It also recognizes the transgender community by including the blue, pink, and white stripes of the trans pride flag. Though this flag was designed back in 2018 (by an artist named Daniel Quasar from Portland, Oregon), the design is especially important this year in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests and the growing recognition of the challenges faced by the transgender community.

– – –

[1] Language around LGBTQ identities is constantly evolving. Today, the term transgender is an adjective used to describe a person whose gender identity does not match the sex they were assigned at birth. Transvestite is a term that is no longer in favor; historically, it was used to describe a person who dressed in clothes that are associated with members of the opposite sex. Because transgender (or trans, for short) is the preferred term today, as well as the term that is used in most biographies of Marsha Johnson’s life, it is the term I have chosen to use in this piece. Additionally, I have used she/her pronouns throughout, as multiple sources seem to agree that these were Johnson’s preferred pronouns. For a more detailed explanation of terminology used to describe transgender identities, check out this article.

[2] A drag performer is someone who performs shows (plays, musical acts, etc.) dressed in clothing that is traditionally associated with the opposite sex. More specifically, a drag queen is usually someone who identifies as a man, but dresses in traditionally feminine clothing for a specific performance, while a drag king is usually someone who identifies as a woman, but dresses in traditionally masculine clothing for a particular performance (This is not a hard-and-fast rule, as someone might identify their gender as non-binary, but still perform drag, for example). In the case of the Jewel Box Revue, DeLaverie was the only woman in the group and consequently, the group’s only “male impersonator,” as it was called at the time. It is worth noting also that drag performers do not necessarily identify as LGBTQ, though historically drag has been associated with LGBTQ culture. This page provides further explanation of the terms surrounding drag.

[3] For reference, the first state to legalize same-sex marriage was Massachusetts, which did so in 2004. Marriage equality was not legalized at a national level until 2015.

[4] DeLaverie was actually never issued a birth certificate because interracial relationships were still illegal in 1920 when she was born. There are people still alive today who were affected by this de jure racial discrimination!

[5] There were too many sources to be able to hyperlink them all in the same sentence, so I will include them here. This website gives a good overview of challenges faced by the transgender community, with emphasis given to issues at the intersection of gender identity and race. At a national level, it is now illegal to discriminate against an employee based on LGBTQ identity, thanks to a Supreme Court Decision that was made literally last week. Still, the fact that this Supreme Court case needed to be ruled on suggests that LGBTQ workplace discrimination has long been an issue, and it will likely take a while for this legal change to result in cultural shifts at many workplaces. This article sheds light on youth LGBTQ homelessness, with statistics about LGBTQ youth of color. This article gives some important statistics on LGBTQ disparities in healthcare, while this one addresses healthcare disparities among Black communities. Finally, this page from the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explains racial disparities related specifically to COVID-19, and this article addresses why some members of the LGBTQ community may be especially vulnerable during this pandemic.